Banking crisis: A New Wave of Regulation ?

Potential Contagion Impacts of the Banking Crisis on Regulation

At a time when governments and regulators are busy assessing financial stability, we consider what the potential impacts could be on the regulatory framework. When the last financial crisis occurred, the G20 summit in Pittsburgh in 2009 reviewed the drivers of the crisis, and the G20 reached a number of commitments. Whether the response to the current crisis will be as global in nature remains to be seen, however current events, both in the US and in Switzerland, pose a number of challenges to a regulatory framework that was, previously, perceived as near-mature.

When we refer to the regulatory framework, our main points of reference are the UK, the EU, and global bodies, such as Basel. This is not intended to be a complete evaluation of lessons learned, sufficient time has not yet passed to enable that, and neither are all the underlying issues clear, rather it outlines some areas of potential focus.

Individual Accountability

It has been widely reported in the press that Silicon Valley Bank was without a Chief Risk Officer for much of 2022. In the UK, under the Senior Managers and Certification Regime (“SMCR”), for certain firms, including banks and Enhanced Scope Firms, the apportionment of the Risk Oversight responsibility is mandatory. Senior Management Functions under SMCR include the Chief Risk Officer Function (SMF 4) and Chair of the Risk Committee Function (SMF 10).

Given there is no specific designated Senior Management Function for the Head of Treasury, firms should ensure that responsibilities in respect of liquidity are clear. Often, there can be overlap between the responsibilities allocated to the Chief Risk Officer and the Chief Financial Officer, across both capital and liquidity matters. Firms should ensure, as a minimum, responsibilities in respect of compliance with capital and liquidity requirements, as well as actual oversight of liquidity management, are clearly apportioned.

In the UK, the Chancellor of the Exchequer announced a series of reforms, termed ‘The Edinburg Reforms,’ which are designed to promote growth and the competitiveness of the UK economy, including a sweeping reform of SMCR, however the current crisis highlights the importance of individual accountability and the apportionment of responsibilities.

A number of other jurisdictions including Australia, Hong Kong, and Singapore, have already implemented local versions of Senior Managers’ Regimes (as well as other apportionment and corporate governance requirements). Applying global standards in respect of individual accountability should be an easier win for the G20, given more jurisdictions have already sought to adopt these standards.

Liquidity Rules

One of the root causes of the banking crisis in the US was the sudden and – for many unexpected – significant shift in interest rates over a period of less than a year. Much has been written of capital and liquidity rules over the past few weeks, including the potential to apply more stringent measures to non-GSIB banks, as well as making capital and liquidity rules themselves more stringent.1 Whilst regulators are likely to review capital and liquidity rules, at a time when the UK was already looking to increase the ‘effective use of capital’ and to reform the regulatory framework,2 it is important to consider the context of the current crisis, and the role that government bonds have played. The inclusion of national government debt securities, without consideration of interest rate risk, in the definition of liquid assets should be considered. Greater focus should be applied on regular testing of the liquidity of liquid assets, and governments may, in future, need to consider making greater use of floating rate debt instruments in order to raise capital.

The Financial Stability Board assessed the implementation of Basel III measures in its annual report on global financial stability. 3 The report identified some issues in the ‘uneven’ adoption of Basel III measures, though not specifically in relation to liquidity ratios. Material risks were, however, identified in respect of financial stability, including high debt levels across sovereigns (as well as corporates and households), which have the potential to impact the resilience of the banking sector. The report specifically stated that ‘potential strains in non-financial sector debt servicing could adversely impact bank asset quality and lead to significant credit losses’.4 The report also identified that further stresses in bond and repo markets could impact financial markets.

Liquidity rules are intended to support banks in stressed scenarios (a stressed scenario refers to ‘a sudden or severe deterioration in the solvency or liquidity position of an institution due to changes in market conditions or idiosyncratic factors as a result of which there is a significant risk that the institution becomes unable to meet its commitments as they become due within the next 30 days’). 5

The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision adopted the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (“LCR”) as part of the Basel III package of measures, to increase bank resilience. The LCR comprises Liquid Assets (or Stock of High Quality Liquid Assets ((“HQLA”))), divided by Net Liquidity Outflows over a 30 calendar day stress period, and banks subject to these requirements are required to maintain an LCR of at least 100%. Liquid Assets (or the Liquidity Buffer in the UK) is made up of both Level 1 and Level 2 assets (subject to limitations and haircuts), and is intended to support firms with covering any imbalances in their liquidity inflows and outflows under gravely stressed conditions over a period of 30 days.

The Regulatory Consistency Assessment Programme (“RCAP”) was established to monitor the implementation of Basel III reforms, and is responsible for publishing an assessment of the adoption and implementation of the LCR, as well as other Basel III standards.6 An assessment of Basel III implementation of the US in 2017 found that the US was compliant with LCR requirements.7 The US applied LCR to 37 institutions in total (comprising the ’15 internationally active bank holding companies and 22 internationally active depository institutions,’) 8 and not only to the eight G-SIBs.

The detailed issues raised by RCAP in respect of HQLA were limited to the inclusion of securities relating to Farm Credit System Administration (“FCA”) and Federal Home Loan Bank (“FHLB”) being included as Level 2A Liquid Assets, as these ‘exposures [were] not “guaranteed by the full faith and credit of the US central government.”’ 9 The other minor issue was the distribution of HQLA by currency.

Whilst it will be tempting to make changes to the regulatory framework to apply the LCR requirements to all banks, and, in the US, not just the 37 firms currently in scope, further consideration should be given to whether these measures would have supported the impacted banks with an orderly wind down, without government intervention. The definition of HQLA is important. It includes marketable securities that represents claims or guarantees by sovereigns or central banks. The requirements state that for assets to be considered HQLA, they must ‘be easily and immediately [convertible] into cash at little or no loss of value.’

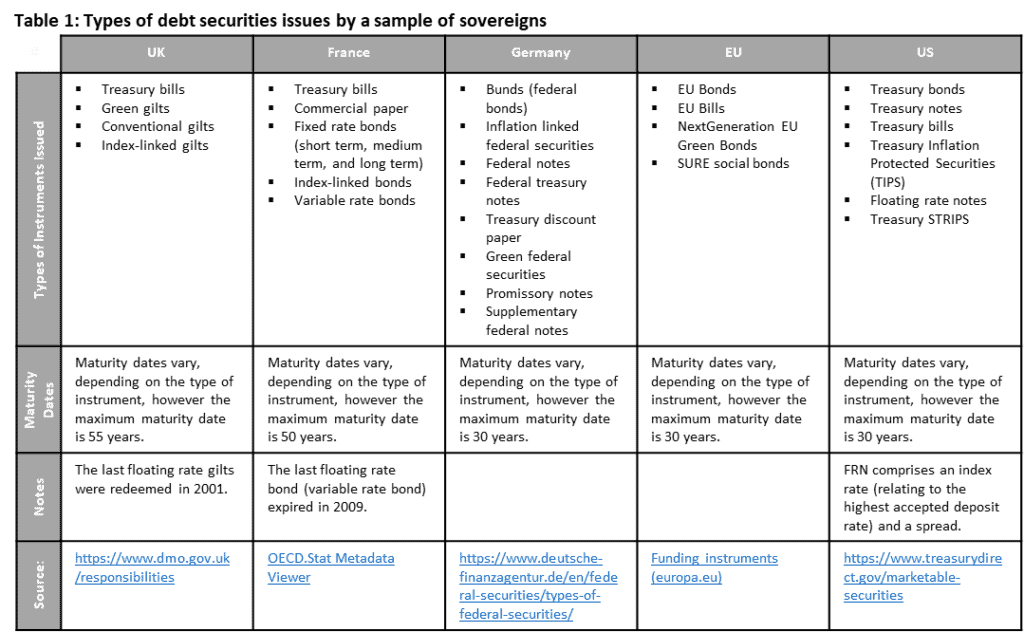

At a time of rising interest rates, the ability to convert government securities into cash at little or no loss of value is difficult to prove, as investors in UK gilts found in September 2022, when the Bank of England had to implement a purchasing programme, directed at purchasing long-dated conventional gilts, and then index-linked gilts, to stabilise demand. However, the value of gilts with long-dated maturities, with lower coupons than the Bank of England base rate, has not recovered. This poses a challenge to the ability of banks to demonstrate that they are able to convert government issued debt securities at little or no loss of value. The issue has been exacerbated by many governments not issuing floating rate debt, the last floating rate gilt in the UK was redeemed in 2001.

HQLA comprises both Level 1 and Level 2 assets, the latter is further subdivided into Level 2A and 2B assets. It should be noted that Basel measures still permit banks to include corporate debt (with credit ratings of AA or above) as Level 2A or Level 2B. When the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive was updated, and implemented in January 2018, bonds, unlike equity and certain derivatives, were not considered sufficiently liquid to support a Mandatory Trading Obligation. There is scope in the regulatory framework to further parameterise the use of corporate debt as Level 2 assets. As banks continue to comply with LCR requirements as far as they relate to regular monitoring and testing of whether assets meet the liquid test, then issues stemming from current calculations of LCR should be limited. However, the FSB report highlights growing issues in repo markets, which could further challenge the ability of liquid assets to pass the liquidity test.

It should be noted that it is not only banks that are impacted. In the UK, investment firms are also required to comply with certain liquidity thresholds, such as the Basic Liquid Assets Requirements (“BLAR”).10 The definition of Core Liquid Assets, under BLAR, also includes government debt securities (i.e. gilts in the UK). Units or shares in a Short-Term Money Market Fund are also considered a Core Liquid Asset. We note the FSB has also cited liquidity mismatches, caused by investor redemptions, in money market funds and investment funds as an area of concern.11

Therefore, investment firms should also be closely monitoring their liquidity metrics.

Whilst government debt securities have provided financial institutions with an easy source of liquid assets, and governments with readily available source of funding, they pose certain risks at times of stress in financial markets. There are a number of options available. For markets to prevail, we expect there will be greater scrutiny of the assets banks and investment firms are holding as HQLA or Core Liquid Assets, respectively. This includes testing the ability of these firms, including investment firms who have not all been subject to the rigours of such testing, to easily convert their liquid assets through repo markets. Governments may also be pushed to consider the ways in which they finance themselves, and the structure of their securities. The use of floating rate debt securities may increase the cost of borrowing for governments, however it could resolve bank liquidity issues. The definition of securities considered liquid, for purposes of HQLA and Core Liquid Assets, could be tightened, with greater weightings applied to floating rate and/or shorter maturity government debt securities to ensure liquid assets pass the liquidity test. Governments may have to join retail consumers in the joys of borrowing during times of rising interest rates.

Investor Protection

The overall impact of the banking crisis on retail clients has, thus far, been limited. However, the cancellation of AT1 bonds during the acquisition of Credit Suisse by UBS has been under scrutiny. Whilst the G20 commitments in 2009 were largely focussed on market structure and transparency, a raft of investor protection requirements were introduced over the last decade, alongside market structure and transparency changes.

In the EU, the Packaged Retail and Insurance-Based Investment Products (“PRIIPs”) Regulation, as well as enhanced requirements introduced under the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive and Regulation (together referred to as “MIFID II”) and the Insurance Distribution Directive (“IDD”), were intended to ensure retail customers were provided with the information they needed to make informed investment decisions, and to be able to compare costs and charges. In the UK, the government has recently announced, as part of the Edinburg Reforms, that it intends to replace PRIIPs.

However, it was assumed that retail investors do not require the same protections when they seek to invest in non-complex and/or non-packaged securities. In short, this means that when retail investors make their own investment decisions in respect of equities and bonds (e.g. AT1 corporate bonds), they do not receive the same level of information (i.e. a Key Information Document) nor the same protections conferred by appropriateness tests, as they would do if purchasing a packaged product. It should be noted that the definition of non-complex does consider the risk posed by certain cash securities, however there is room for interpretation by firms. It should be noted that even UK gilts carry a risk for retail investors at a time of interest rate rises.

There are steps being taken in the UK to move to a more outcomes-focussed application of investor protection requirements through the introduction of a Consumer Principle, which will be supported by the Consumer Duty. The Consumer Duty is intended to ensure a higher standard of care is provided by firms to consumers. The Consumer Duty cross-cutting rules will mean that firms will need to demonstrate that they are acting in good faith, that they are avoiding causing foreseeable harm, and that they enable and support retail customers to pursue their financial objectives.

Over the coming months, and years, we expect greater focus on investor protection. Whether the UK will include bonds in their package of reforms to replace PRIIPs remains to be seen, or introduce other explicit requirements, given the application of the Consumer Duty, however we expect the EU to start considering the broader implication of the current crisis on investor protection requirements set out in PRIIPs and MIFID II, including whether bonds, and some equity structures (e.g. Class B shares), should be considered sufficiently complex, at a time when more retail investors have started to invest directly in markets, to merit the extension of PRIIPs to cover these instruments and the definition of non-complex products under MIFID II, for purposes of the appropriateness test, to explicitly remove these instruments from its scope.

Conclusion

Individual accountability remains important. There is likely to be greater scrutiny and, we would expect, greater international alignment in this area. The outcomes of the SMCR Review should recognise the work firms in the UK have done to implement these requirements. Firms already subject to individual accountability requirements, such as the SMCR in the UK, should ensure that responsibilities between the CFO and the CRO are clearly articulated. This should include responsibilities for ensuring compliance with requirements, such as liquidity rules.

Whether any changes will be made to US capital rules, and the use of mark-to-market, will be subject to much debate over the coming months. It may be tempting to apply the full suite of Basel III measures more broadly to all banks, irrespective of the systemic risk posed by the bank. However, underlying issues, even if all banks were required to maintain an LCR of 100%, could still result in liquidity issues, and systemic liquidity risk, in an environment of rising interest rates and government debt pressures. Regularly testing the liquidity of HQLA would not resolve this issue.

The RCAP report on the US identified two issues in respect of HQLA, including the inclusion of the FCA and FHLB securities in HQLA, and the distribution of HQLA by currency. The report did not highlight any further issues at a time, when low (and for some countries negative) interest rates were prevalent. The definitions of HQLA and Core Liquid Assets should be revisited to increase financial sector resilience, and, where required, force governments to review the structure of their debt financing (though this would add to debt servicing pressures, at a time when debt-to-GDP ratio is high). Whilst some have called for a return to lower interest rates, reducing interest rates in the short to medium term may stabilise the price of government bonds, however it does not deal with the real issue of how liquid assets are defined, when a more dynamic definition, with appropriate risk weightings applied under different scenarios, could support banking resilience in the long term.

The prudential treatment of sovereign assets has been under focus before,12 we expect the current crisis could lead to a broader review of the prudential treatment of sovereign exposures (including applying risk weightings depending on the maturity and structure of bonds utilised for liquidity risk management, and potentially a greater consideration of sovereign-related credit risk in the capital requirements regime). Regulators may also re-consider existing assumptions that underly current Interest Rate Risk in the Banking Book (“IRRBB”) requirements and practices under pillars 2 and 3. In the interim, however, Firms (including both banks and investment firms) should expect greater regulatory focus on their liquid assets.

Further work is required on investor protection. At the point of trade execution, in the EU and UK, firms are not required to provide retail investors with key information in respect of the risks and limitations of certain securities, such as bonds, in as much detail as they receive for packaged products. Not all retail investors, in the current age, would pass the ‘reasonable investor’ test, and as we have seen from the experience of AT1 bonds, neither are these investments the types of securities that those we view as reasonable investors would be able to review and assess the risk of, without the relevant product documentation at the point of sale. Therefore, further changes may still be required to investor protection requirements.

This is by no means an exhaustive assessment of potential changes to the regulatory framework, or what the next set of global commitments (if any) at the G20, or regulatory initiatives at the local, regional or global level under FSB and BCBS, might look like. We expect other lessons learned will emerge over the coming weeks and months.